A FLASHLIGHT & A ROLL OF TOILET PAPER

Costa Rica was still a third-world country when I first came here over 50 years ago, and part of me wishes it still was. Some of my most treasured memories are from that period in the early 1970s when I worked on a large ranch on the Caribbean side of the country. It was only accessible by a narrow-gauge railroad called the Northern Railway. I hadn’t been there long when I met a great guy, an Englishman by the name of Johnny James who came to Costa Rica in the 1930s, before the concept of the third world had even come into being.

I once accompanied him on a four-day adventure, during which I learned much of what I know about the Caribbean side of the country. It all began in a place called El Cairo in a restaurant owned by Juan Quiros Ching. No sooner had we finished our coffee and empanadas than the owner of the burro carro, our mode of travel for the first leg of the journey, walked in and shouted to Johnny that he was ready to go. The burro carro was a small platform with four railroad wheels. It was drawn by a mule. During the hour it took to reach the creek at the end of the spur, Johnny talked non-stop. “Years ago,” he began, “the immigration of Chinese to Costa Rica was prohibited by law. But what can I say; you know how it works. Laws are for common people like you and me, not for the wealthy, especially not back then. At the beginning of the century lots of Chinese were brought here to work as indentured servants in the households of well-to-do Costa Rican families. After a certain number of years of unpaid service, their debt was fulfilled, and their masters had to free them. Most took the last names of those same former masters and eventually acquired Costa Rican citizenship. Just like Juan Quiros”, Johnny continued. “He and his wife were betrothed as children and came to Costa Rica from China at the age of ten or eleven. To put it bluntly, their parents sold them to a rich Tico. They had to work for fifteen years to earn their freedom. Then they moved out here to the jungles of the Caribbean, along the railroad, and proceeded to make their fortune. They worked their butts off, but today they’ve got the business, a farm, and a pile of money”.

I once accompanied him on a four-day adventure, during which I learned much of what I know about the Caribbean side of the country. It all began in a place called El Cairo in a restaurant owned by Juan Quiros Ching. No sooner had we finished our coffee and empanadas than the owner of the burro carro, our mode of travel for the first leg of the journey, walked in and shouted to Johnny that he was ready to go. The burro carro was a small platform with four railroad wheels. It was drawn by a mule. During the hour it took to reach the creek at the end of the spur, Johnny talked non-stop. “Years ago,” he began, “the immigration of Chinese to Costa Rica was prohibited by law. But what can I say; you know how it works. Laws are for common people like you and me, not for the wealthy, especially not back then. At the beginning of the century lots of Chinese were brought here to work as indentured servants in the households of well-to-do Costa Rican families. After a certain number of years of unpaid service, their debt was fulfilled, and their masters had to free them. Most took the last names of those same former masters and eventually acquired Costa Rican citizenship. Just like Juan Quiros”, Johnny continued. “He and his wife were betrothed as children and came to Costa Rica from China at the age of ten or eleven. To put it bluntly, their parents sold them to a rich Tico. They had to work for fifteen years to earn their freedom. Then they moved out here to the jungles of the Caribbean, along the railroad, and proceeded to make their fortune. They worked their butts off, but today they’ve got the business, a farm, and a pile of money”.

At the end of the spur, the man who brought us, unhitched the mule, took it around and hitched it to the other end of the burro carro, and returned to El Cairo. A small boat with a tiny outboard motor was waiting. “We need to get going” urged the boatman. “It’s getting late”.

We had the current in our favor, and we made it to Parismina just before nightfall. Dinner was delicious, steamed vegetables, rice, and chicken, prepared by the owner of a pulperia (general store), a friend of Johnny’s and fellow countryman of Juan Quiros. We slept in a couple of upstairs rooms. The next day we puttered on in our little boat through the canals to Tortuguero where a talkative lady, hungry for news, fixed us a tasty lunch of white-lipped peccary in tomato sauce with rice and beans which we ate on a table on her front porch. From there we proceeded on to Limón where we boarded the southbound train.

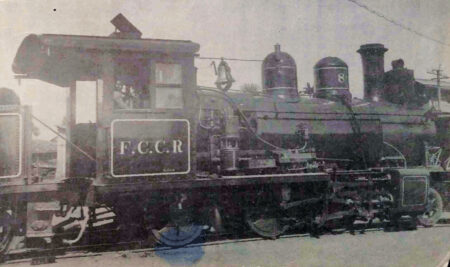

During the train ride Johnny explained that the Atlantic railroad was owned by the Northern Railway Company, which was founded by a British industrialist named Minor Keith, the man generally credited with accomplishing the gargantuan task of constructing Costa Rica’s first railroad. The project was begun in the early 1880s and completed in 1891. Partially financed by United Fruit Company, the railroad made banana production feasible in the Atlantic zone.

Keith soon found that Costa Rican workers had little resistance to malaria and yellow fever and would not be able to provide the labor for building the railway, so he brought in laborers from Jamaica. The Jamaicans were good workers and had a long history of resistance to tropical diseases. Had it not been for them, the Atlantic railway might never have been completed. Nevertheless, they were given little in the way of appreciation for their contribution to Costa Rica’s development. Even Jamaicans born in Costa Rica were, for years, considered to be Jamaican citizens and were not afforded the same rights as Costa Ricans. At first, they were allowed to travel no farther west than Peralta, a small town between Siquirres and Turrialba. Later they were allowed to go as far as Turrialba, then Cartago, and finally to San Jose and the rest of the country. Eventually the Jamaicans were given citizenship and all the rights that came with it.

We stepped off the train at a place called Penhurst. Before we could continue to Cahuita, our destination for the night, we needed to cross the Estrella River. This was accomplished in a small boat called a cayuca, which was propelled by a boatman with a long pole. The bus was broken down, so we were met by a truck instead. I remember the driver brushing his teeth in the muddy river water. A light rain started falling as we climbed into the back of the open bedded truck. I noticed that the Tico truck driver and his two black companions were speaking a language I didn’t understand. “It’s a local dialect”, Johnny explained. The older Jamaicans speak only English and the younger ones English and Spanish, but everybody speaks patois, except us outsiders”. About the time we arrived in Cahuita, the rain stopped. After a delicious dinner of rice and beans and fish cooked in coconut oil by a delightful Jamaican man, who was determined to sell me a lot on the beach, we slept in the only hotel in town.

The bus was working the next day and took us on a morning excursion through the countryside. It broke down again just outside of Puerto Viejo. We hiked into the village and found a guy with a Toyota pickup who took us back to Cahuita where we had a relaxing, uneventful afternoon. The next morning, we returned to Penhurst the same way we came. The rest of the trip home was by rail with one change of trains in Limón and another in Siquirres.

My four-day adventure with Johnny James ended in El Cairo at dusk. During dinner at Juan Quiros Ching’s restaurant Johnny offered a bit of wisdom. “You’re a good listener,” he remarked casually. “Now you know a bit more about this part of the country. I have a feeling that you’re gonna be in Costa Rica for a long time, maybe even the rest of your life, and you’re gonna have plenty of adventures. Just a bit of advice from an old-timer; wherever you go, take a flashlight and a roll of toilet paper, and you will survive.”

Jack Ewing was born and educated in Colorado. In 1970 he and his wife Diane moved to the jungles of Costa Rica where they raised two children, Natalie and Chris. A newfound fascination with the rainforest was responsible for his transformation from cattle rancher into environmentalist and naturalist. His many years of living in the rainforest have rendered a multitude of personal experiences, many of which are recounted in his published collection of essays, Monkeys are Made of Chocolate. His latest book is, Where Jaguars & Tapirs Once Roamed: Ever-evolving Costa Rica.