Chocolate Addiction isn’t Exclusive to Humans

Lots of Wild Animals Love Cacao Seeds

By Jack Ewing

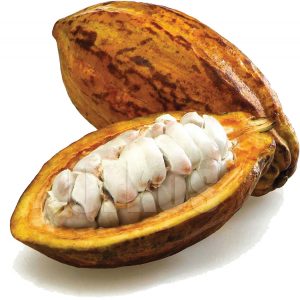

More than a dozen years ago when I wrote the original article “Monkeys Are Made of Chocolate” for Quepolandia, little did I know that it would later become chapter one of a book by the same name. It talked about the unexpected effect that the increased availability of cacao seeds had on the general health and population of white-faced monkeys. In summary the article said that when we abandoned our nine hectares (22 acres) of cacao plantations at Hacienda Barú, due to a market plunge, the monkeys immediately moved in and started chowing down on cacao seeds. As a result of this windfall of nutrition the white-faced capuchins no longer had to struggle to survive, rather they got fat and happy and started having more babies than ever. The article goes on to compare this to humans and has an interesting message at the end. When I wrote that article I was only beginning to understand the complexity of a cacao plantation that has been given over natural processes. Man can plant cacao for the production of chocolate for the exclusive consumption of humans, which all of my fellow chocolate lovers will appreciate, but only Mother Nature can exploit it to its fullest. One of the most researched protected areas in Costa Rica is a huge nature reserve called “La Selva Biological Station.” A biologist friend once told me that the most biologically diverse areas of La Selva were the old abandoned cacao plantations, not the primary forest that one might expect. This got me to thinking and paying more attention to our old cacao plantations at Hacienda Barú which have not been pruned or otherwise cared for since 1986. I soon figured out that the cacao producing trees were planted only four meters apart, and that nowhere in a natural forest do we find such a concentration of nutrients.

Wastefulness

Early on during my 46 years of experience with the Costa Rican rainforest I noticed how wasteful white-faced capuchin monkeys usually are. Their normal mode of eating anything is to grab a handful, stuff part of it in their mouths, and throw the rest on the ground. With a cacao pod they pluck the pod, weighing up to one kilo, take a bite out of one side or bang it against a branch to break it open, eat a few seeds, throw the rest on the ground, and pick another pod. Wasteful right? One of our guides observed a group of monkeys on the ground messing around with fallen cacao pods. Upon closer examination he realized that the pods were full of protein-rich maggots which the monkeys were eating. Not as wasteful as I had thought. At first there was little competition for the fallen pods. Later pacas, agoutis,coatis, spiny rats, and peccary discovered them. What is left after all of these animals are finished is consumed by ants, fungi, bacteria, and other minuscule forms of life. Absolutely nothing goes to waste. Even the trace minerals found in the cacao pod are incorporated into the soil and are utilized by other organisms, mainly plants.

Monkeys also prey on squirrels and their young, so the squirrels only make occasional incursions into the old plantations, and never nest there. Their reason for being there is to eat the nutrient-rich cacao seeds which they do by chewing a hole in the pod without removing it from the tree, digging the seeds out with their front paws, and eating them. As you might imagine many seeds fall on the ground while the squirrel is eating. Those seeds remaining in the pod once the meal is finished gradually loosen up and fall out of the hole onto the ground. Again, nothing in the natural world goes to waste. Those animals already mentioned and several others gobble them up as soon as they find them. Peccaries and coatis rout around in the leaf litter and loose soil which is rich in organic matter, and eat the seeds along with many forms of small animal, fungal, and plant life found there.

Termites

A pair of slaty-tailed trogons, breathtakingly beautiful rainforest birds, were often seen near an old abandoned cacao plantation. Because of their secretiveness it took us a couple of years to figure out where they were nesting. Termites eat dead wood, but don’t bother the living wood. Their nests are large, dark, brown or black globs which are found on many cacao trees in old plantations. When the plantations are being cared for, all the dead wood is pruned away, and there is nothing left for the termites. We discovered that the trogons were burrowing into the center of these hard, brittle nests and hatching and caring for their young in a hollowed out cavity within the termite’s abode. Parakeets and some of the smaller parrots also take advantage of the termite nests for the protection of their eggs and chicks.

When a Hacienda Baru guide is conducting a tour that passes through an old cacao plantation, he/she will often eat a termite and offer one to each of the guests. The closest I can come to describing the taste is that it strongly resembles peanut butter. I guess geckos, and a multitude of other little lizards like peanut butter because they frequent the branches where the termites are found, break open the tunnel-like trails, and eat the termites as they scurry around trying to repair the damage. We have noticed several different species of hawks in the plantations, and, upon careful observation realized that they are there mainly to feed on these small lizards.

Boas are often seen coiled up in the branches of the cacao trees. Their main prey are squirrels, opossums, and rats. Sloths don’t eat cacao leaves, but they do eat the leaves of some of the shade trees found in the plantations, and are frequently found there. Many of those shade trees are a species called poró which produces hundreds of a nectar-laden, orange flowers. Monkeys love to eat the flowers and humming birds are attracted to them like flies to sugar. One ornithologist counted 11 different species of humming birds in one heavily flowered poró tree. Costa Rican wild turkeys called great curassows scratch around in the leaf litter and lose soil looking for seeds, insects, and other minuscule forms of life. Litter frogs and occasionally poison dart frogs can be found on the moist ground as well. In addition to all of the animals mentioned previously our trail cameras have captured videos of grouse-like great tinamous, armadillos and also ocelots in the old cacao plantations.

This morning, October 9, 2016, I went with Hacienda Barú guide Cristian into an old cacao plantation hunting for photos for this article. It was an incredible hike. First a collared peccary appeared like magic in the middle of the trail, looked around and casually wandered back into the trees on the other side. About 15 minutes into the hike we encountered a troop of monkeys feeding in a group of heavily fruited trees. We observed a young monkey pluck a cacao pod and repeatedly bang it against a branch to break it open. Half the pod fell to the ground while the monkey fished for seeds with its fingers in the other half. Shortly another young monkey showed up and tried to steal the half pod from the first. Not surprisingly it fell to the ground during the fracas. With nothing to fight over they each went on their own merry way. “Look,” said Cristian, “a mother and baby agouti.” They were happily eating the fresh seeds that the monkeys had dropped. In the lower branches a gray-headed tanager flitted around grabbing the insects that the unruly monkeys stirred from their hiding places. The whole experience clearly illustrates the reasons for my ongoing love affair with tropical nature.

Anyone who would like to read the complete article mentioned at the beginning of this article can write to me at [email protected] or, better yet, you can buy a copy of Monkeys Are Made of Chocolate and read chapter one and 31 other interesting stories. It is available from www.amazon.com or www.pixyjackpress.com.