Fiddlin’ Around – May/June 2018

Usually at some point in my articles I nag you folks to get out and listen to real people playing music together, and there are good reasons for my nagging! Now of course this is partly self-serving, as I play around here a lot and I totally prefer to play for people as opposed to empty chairs. Most musicians love it when an audience is receptive and having fun and getting into the music, but it’s also because something special happens during live performances. It’s a one-time-only kind of deal that will never be repeated in exactly the same way. A live show is always unique, no matter how rehearsed or scripted or pre-meditated it might be. Part of it is the energy and spirit coming from the audience. Part of it is the time and place. Part of it is the communication between the musicians. Maybe it’s about the moon or how much sleep the players got the night before or how many cups of coffee they’ve had or whether the guitar player is getting along with the drummer, but it will never happen exactly the same way again.

Usually at some point in my articles I nag you folks to get out and listen to real people playing music together, and there are good reasons for my nagging! Now of course this is partly self-serving, as I play around here a lot and I totally prefer to play for people as opposed to empty chairs. Most musicians love it when an audience is receptive and having fun and getting into the music, but it’s also because something special happens during live performances. It’s a one-time-only kind of deal that will never be repeated in exactly the same way. A live show is always unique, no matter how rehearsed or scripted or pre-meditated it might be. Part of it is the energy and spirit coming from the audience. Part of it is the time and place. Part of it is the communication between the musicians. Maybe it’s about the moon or how much sleep the players got the night before or how many cups of coffee they’ve had or whether the guitar player is getting along with the drummer, but it will never happen exactly the same way again.

Thanks to Thomas Edison, a recording device was invented which brought music and speech to listeners with the proper equipment. Later, flat records evolved which remained the playback medium for the next 60 years or so. There were reel to reel tapes, and cassettes and 8 tracks and CDs. The radio brought previously recorded music to the masses, and nowadays there are many ways to hear music through the internet, whether it be live broadcasts or the recording some guy with a ukulele made in his basement. With a click on your computer you can hear radio stations from all over the planet, or download stuff from years past or last nights’ show. But standing in front of a speaker listening to a band playing live is still a special and wonderful thing.

I like doing studio work, but it requires a different set of skills, equipment and approach than playing live. Many times I have been called in to a studio to play just a few pertinent parts, never really hearing the whole song or knowing what it was about. The recording part of my career started back when actual tape was used to record onto, and the mixing part was as important to the ultimate sound as was the musical content. Sometimes we tried to record as many of the instruments and vocals at the same time, striving for a ‘live’ sound. Sometimes all the parts would be recorded separately onto their own track, cleaned up later of any unwanted noise, adjusting the volume levels and tone of the instruments or vocals, then it would all be finalized in the mix. Engineers who were really good at mixing would make notes about little details—where to turn up the singers volume for 5 seconds, or erase an unwanted cymbal crash or brighten up the horn parts for a short time. Back then, when you made a final mix it often involved several people manipulating the tracks, and sometimes the mix was inspired and everyone worked beautifully together. Sometimes it was lackluster and stiff or over-produced. I can remember the tension and cooperation between the studio engineers and the musicians when doing a final mix—there might be half a dozen people hovering over the mixing board, each with their role to play. Now you can do anything you dream up in the studio and there is no ‘final’ mix that can’t be changed. If someone sings one note that is flat, you can isolate that note on the computer, correct the pitch and save that adjustment to the computer and never have to worry about it again. Or worry about the singer hitting the right note. All the technical advances have in some respects made recording much easier, but you can also lose that ‘live’ enthusiasm and spontaneity in the process and end up with robot music.

Get away from electric lines and sit quietly in the jungle and listen. Listen to the chorus of crickets, frogs and birds and it will seem like they are listening to each other. It’s as if the different species take turns singing, with an invisible conductor cueing them all. When the critters sound like they’re in unison, they still emit different tones and pitches and it does seem to be mysteriously orchestrated. Introduce an artificial sound into our jungle mix, like a car horn or the noise from a plane or a gunshot, and most everything will go silent. Eventually the animals will all strike up again, but they do so in fits and starts—almost as if they don’t know when to come back in and no one’s leading the band. These interruptions caused by noise pollution can produce disastrous results. There’s an endangered species of frogs that use their unison sound to fool their predators. When they are all singing together they sound like a much larger animal, so they are left alone. As they come back in singly, they are left exposed and they get picked off, one by one. It’s well documented that animals which are constantly subjected to artificial sounds or vibrations have mental, physical and re-productive problems.

Get away from electric lines and sit quietly in the jungle and listen. Listen to the chorus of crickets, frogs and birds and it will seem like they are listening to each other. It’s as if the different species take turns singing, with an invisible conductor cueing them all. When the critters sound like they’re in unison, they still emit different tones and pitches and it does seem to be mysteriously orchestrated. Introduce an artificial sound into our jungle mix, like a car horn or the noise from a plane or a gunshot, and most everything will go silent. Eventually the animals will all strike up again, but they do so in fits and starts—almost as if they don’t know when to come back in and no one’s leading the band. These interruptions caused by noise pollution can produce disastrous results. There’s an endangered species of frogs that use their unison sound to fool their predators. When they are all singing together they sound like a much larger animal, so they are left alone. As they come back in singly, they are left exposed and they get picked off, one by one. It’s well documented that animals which are constantly subjected to artificial sounds or vibrations have mental, physical and re-productive problems.

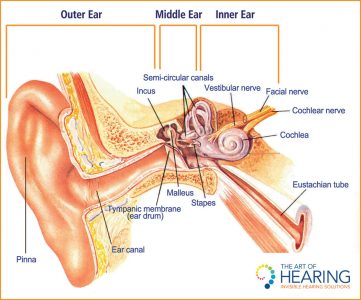

A youthful human ear can hear ten octaves of sound, spanning a range of about 30 to 12,000 vibrations per second. From the top of the tonal spectrum to the bottom, we hear about 1,300 different tones. Although the inner ear is well protected from most injuries, it is highly vulnerable in other ways. Every siren, airplane roar or cymbal crash does exact a cost, especially to the delicate hair cells. Listening to music in an already noisy environment (like with headphones), or using it to drown out other noise almost guarantees that it will be destroying hair cells. So you might as well save those cells for when you need them—like when you are standing in front of a smokin’ hot electric guitar player casting out his demons, or when your head is stuck in the bass drum or when the soprano hits that high note!

Many music business folks said good-bye recently to one of the best engineers and producers of live performances ever—an unassuming and righteous and wonderful men named Robert ‘Kooster’ McAllister. He ran Record Plant Remote Studios, received a Grammy with his name on it, and was said to have the best set of ears in the business. I am so happy he came down to visit us a couple of years ago—we sat on the front porch and played music and remembered old times and laughed and talked about our shared 40 years of friendship. He would also tell you to get out and listen to LIVE MUSIC! And he should know.

Music, in performance, is a type of sculpture. The air in the performance is sculpted into something. Frank Zappa

Most people are prisoners, thinking only about the future or living in the past. They are not in the present, and the present is where everything begins. Carlos Santana

If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away! Henry David Thoreau

Nice NJ, you nailed it. Brought me back to our early days of recording. And yes, Kooster was the best and is dearly missed.

What a great read. Really enjoy these monthly articles. I feel more informed after each one. Keep the “Fiddlin’ Around” comin’ each month. Reading online from Colorado.