MORE ABOUT SNAKEBITE

By Jack Ewing

In the August issue of Quepolandia I published an article entitled, If You Are Unfortunate Enough to get Bitten by a Snake, Do it in Costa Rica. If you didn’t see it the article is available online at www.quepolandia.com/category/jack-ewing/.So much new information has come to my attention since those words were written that I decided to elaborate on the same theme this month.

The August issue of Quepolandia arrived at Hacienda Baru the same day that my friend and neighbor Randy Burns was bitten by a Terciopelo (Bothrops asper), Sunday, August 2, 2015. He was awakened at 4:00 AM when his dogs started barking. Concerned about what may have triggered the barking Randy got up and walked barefoot onto the front porch of the house. No sooner did he set foot on the porch when he felt a sting on his left ankle and thought he had been bitten by a scorpion. Returning to his bedroom, he illuminated his ankle with a flashlight and saw blood. Thinking it strange that a scorpion sting would draw blood he returned to the porch with the flashlight and a stick and shined the beam around the floor. There was the Terciopelo coiled up in a corner. He tried to hit it with the stick, but the snake managed to escape out into the yard. “Marie, Marie,” he called to his wife. “Hurry! We need to go to the hospital. I’ve been bitten by a snake.”

They called their trusted employee Eliecer, who came running over from his house. Eliecer drove well over the speed limit, and they covered the 30 kilometers to the Hospital Max Terán Valls in Quepos in less than 20 minutes. They pulled directly into the area where the ambulances unload patients. Marie jumped out, ran up to the emergency door and told the first person she saw that her husband had been bitten by a Terciopelo. They rushed Randy straight into the emergency treatment section ahead of everyone in the waiting area. Marie was impressed that there was no wasted time. Everyone knew what needed to be done, and they did it. Hospital personnel drew some lines around his ankle and lower leg with a marker pen so they could determine the level of swelling by measuring the distance between the lines. One of the fangs had penetrated all the way to his ankle bone, and the other entered the soft tissue below it. Forty-five minutes from the time he was bitten by the snake the antivenin started flowing into Randy’s vein.

The pain started about the time they got to the hospital. At first it was little more than an annoyance, but once the antivenin treatment started, it almost immediately became unbearable. “Never in my life have I experienced such excruciating pain,” Randy told me later. They gave him the most potent pain killers they had, short of morphine, but nothing helped. The pain continued. After six hours of misery the doctor gave him morphine. They first had to wait for the other pain killers they had given him to wear off. The morphine finally brought the pain down to a bearable level.

About half an hour after the antidote began flowing into his veins, Randy had an allergic reaction. A sever rash broke out all over his body, accompanied by an itching and burning sensation. The doctor suspended the antivenin and gave Randy antihistamines to counter the allergic reaction. They waited another 30 minutes and began the antivenin again. This was absolutely necessary in order to save his life. This time the reaction was more severe. Again they suspended the antidote and gave him antihistamines. His blood pressure plunged and Randy nearly lost consciousness. “I was sure I was going to die,” he confided in me later. The doctor and hospital personnel managed to pull him through the crisis. They suspended the administration of the antivenin permanently. Marie remembers that they had originally injected five vials of the antidote into a half liter bag of saline solution which dripped into Randy’s vein. By the time the doctor stopped this treatment for good, about 2/3 of the solution was gone. She figures that he received about three vials. Fortunately that was enough, even though all five would have been better. Perhaps the snake didn’t inject a full load of venom. No one will ever know.

Randy was in the emergency room for two days, and was then moved over to a regular hospital room, where he remained for three more days. He was discharged from the hospital on Friday, August 7. The next night he returned because of high blood pressure. “I thought my head was going to explode,” he told me. Twice more he had to return to the emergency room, both times because of excessive pain. One time the pain nearly paralyzed his neck and shoulders. The doctor told him that the powerful antibiotics he had been given to prevent infection from the bite were the cause of his muscle and joint pain. Randy also asked the doctor if many other patients experienced an allergic reaction similar to his. The answer was that only about one case in a hundred is complicated by the allergy.

Once he was home the pain continued to bother him, especially when he walked. When his leg was elevated the pain diminished. The rash and itching from the allergic reaction also persisted. Seven weeks later, when I interviewed him, Randy was still experiencing muscle and joint pain from time to time. At one point patches of superficial numbness appeared at different places over his body. He was still experiencing numbness in mid-October more than two months after he was bitten.

The total bill for two days in the emergency room, three days in the hospital, the three posterior visits, all of the medicines, and the doctors, came to about $7500. Compare this to Mr. Eric Ferguson who reported to the emergency room of a hospital in North Carolina. His snakebite wasn’t too serious, and he needed only four vials of antidote. He was released after 18 hours. His bill was $89,277. He had been charged $20,000 per vial for the antidote and $9277 for the emergency room care.

Fortunately the Instituto Clodomiro Picado in Costa Rica produces enough antivenin to supply the demand in the country and export serum to the rest of Central America, Panama, Ecuador, and Nigeria. They are even collaborating in the production of an antidote for the bite of the Taipan of Papua New Guinea. The quality of their product is excellent as is evidenced by the death rate of less than one-half of one percent, one to two deaths of the approximately 600 victims of snakebite in Costa Rica annually.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) 1.8 million snakebites occur annually worldwide resulting in 94,000 deaths and about three times that many amputations and patients with permanent disability. Most of the deaths are people from rural areas in third world countries who don’t have access to treatment. Each year in Africa 30,000 people die from snakebites. In comparison only about 11,500 people died during last years’ Ebola epidemic.

Though the WHO is aware of the problem, they are doing little to help. For example they issue guidelines for the treatment of 17 different medical disorders including dengue and sleeping sickness, but don’t offer guidelines on the treatment of snakebite which causes more deaths than all of the 17 combined. This means that if a person is bitten in rural Africa they are unlikely to receive treatment. Even if the closest medical facility happens to have the antivenin, the medical personnel will probably not have the knowledge necessary to administer the treatment safely and effectively. According to the non-profit organization Doctors Without Borders, about 95% of the snakebites in Africa take place in rural areas and only about 10% are treated.

The best antivenin for African snakes is a product called Fav-Afrique which used to be manufactured by a French multinational called Sanofi Pasteur. However, they quit producing it in January of 2014 because it wasn’t profitable. The company cited competition from other products as the main problem. Fav-Afrique, when it was available, sold for between $250 and $500 per vial, too expensive for rural medical centers which attend most snakebite victims. Competing products are being produced in Spain, India, UK, South Africa, Costa Rica, and Mexico. According the Doctors Without Borders only the UK product and the Costa Rican product, called Echi Tab Plus, give good results. I don’t know how much the Costa Rican product exported Nigeria costs, but the Polivalent Serum produced by the Instituto Coldomiro Picado costs Costa Rican hospitals about $20 per vial. This is proof that developing countries can produce excellent treatments for the bites of venomous serpents at a reasonable cost.

As I mentioned in the earlier article, the late Dr. Clodomiro Picado Twight (1887 to 1944) was a medical doctor who worked at the San Juan de Dios hospital in San Jose. He is best known for his extensive research into venomous snakes in Costa Rica and the treatment of snakebite. The institute that honors this distinguished physician was founded in 1970. Its creation was a joint effort of the Ministry of Health and the University of Costa Rica. It has grown into an exemplary organization that all Costa Ricans and residents can be proud of.

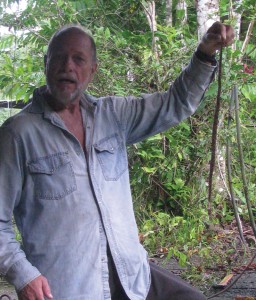

After Randy Burns was bitten by the terciopelo he and Marie received several phone calls from friends and neighbors. Many of these calls came from campesinos who warned them that the snake would return in seven days. Eliecer hunted for it diligently all week to no avail. On the morning of Saturday, August 8 Eliecer’s mother-in-law called to warn them to be very careful because the snake that bit Randy would return on that very day. Later in the morning Eliecer found it in the car port under a hub cap and killed it.