Frijolito, The Killer Squirrel

While sitting at my computer one day, a woman’s scream jolted me from my train of thought, brought me to my feet and hurried me off toward the call of distress. In the living room I found Cecilia, our housekeeper, wringing her hands, blood running down both sides of her face, and tears streaming down her cheeks. She didn’t have to say what happened. It was obvious, but she said it any way. “Fue el asesino,” The killer squirrel had struck again.

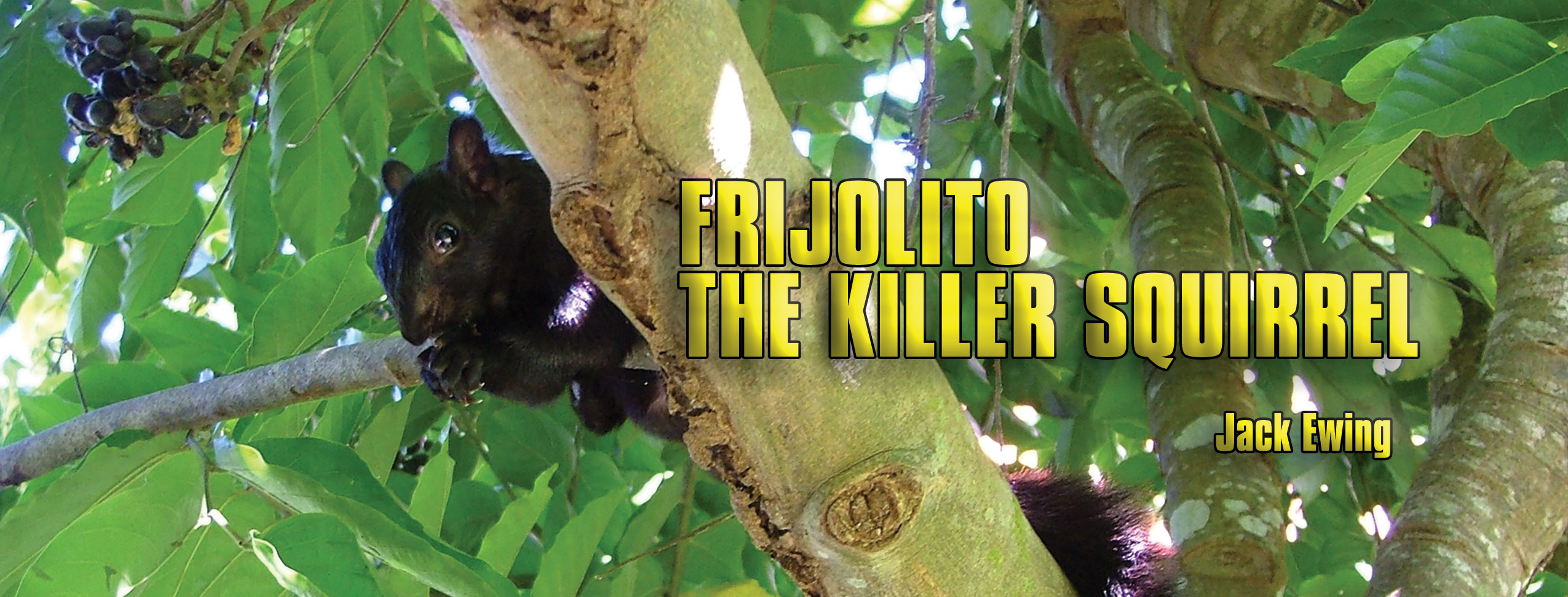

My wife Diane and I both love animals. I love seeing them in the wild, and Diane loves keeping them as pets and caring for them. So, when one of Diane’s dogs found a helpless baby squirrel, about the size of a bean-shaped egg, it promptly became part of her menagerie. Small and black, the name “Frijolito,” meaning “Little Black Bean”, fit him perfectly. Diane nurtured and fed him with a tiny baby bottle and nipple. He grew like wildfire and soon had his eyes open. Later he climbed over our arms and shoulders, and even got up on top or our heads. He was a real charmer, and everyone came to love Frijolito.

My wife Diane and I both love animals. I love seeing them in the wild, and Diane loves keeping them as pets and caring for them. So, when one of Diane’s dogs found a helpless baby squirrel, about the size of a bean-shaped egg, it promptly became part of her menagerie. Small and black, the name “Frijolito,” meaning “Little Black Bean”, fit him perfectly. Diane nurtured and fed him with a tiny baby bottle and nipple. He grew like wildfire and soon had his eyes open. Later he climbed over our arms and shoulders, and even got up on top or our heads. He was a real charmer, and everyone came to love Frijolito.

Diane built a large cage and filled it with tree branches and leaves. Frijolito played on the limbs and learned about balance and clinging tight. He began to eat solid food like papaya, guava, the fleshy part of the almond fruits and all kinds of nuts, but still got a bottle before bed. Came the day when Diane let him climb a real tree. After a couple of falls, a squirrel’s equivalent of the school of hard knocks, Frijolito became proficient at traversing the treetops, but checked often to make sure Diane was still sitting under the tree. As his confidence grew Frijolito ventured farther into the wild. We built a rope bridge from a tree to his cage on the porch, permitting him to come and go at will. Food was available in the cage, and he was free to play in the trees all day. Diane always brought him in at night.

The course of Frijolito’s life was pretty much preordained by the circumstances of his foster home, his instincts, and his testosterone level. The first indications of Frijolito’s emerging violence appeared shortly before his first tree climb. One night after his bedtime bottle feeding, Frijolito was romping and playing on the table and racing over our arms and shoulders. He nearly slipped from Diane’s arm, and she yelled, “Jack, grab him, quick.”

The course of Frijolito’s life was pretty much preordained by the circumstances of his foster home, his instincts, and his testosterone level. The first indications of Frijolito’s emerging violence appeared shortly before his first tree climb. One night after his bedtime bottle feeding, Frijolito was romping and playing on the table and racing over our arms and shoulders. He nearly slipped from Diane’s arm, and she yelled, “Jack, grab him, quick.”

I did, and he bit me hard. I dropped him on the floor, blood spurting from my index finger. Squirrel incisors are sharp. Diane gathered him up quickly, checked him over for damage from the fall and put him to bed.

The first day Frijolito went tree climbing Diane called me over to see. He came down to my eye level on a low hanging branch and wiggled his nose. Remembering that bite, I held out my hand, warily. “Go ahead,” urged Diane, “he wants to give you some loving.”

I moved my hand a little closer. Frijolito sniffed it, grabbed my finger with his claws and bit down twice before I could snatch my hand back. This time there were several lacerations from his incisors and torn skin from his claws. I had never dreamed what an effective weapon a squirrel’s claws could be. “That’s it,” I proclaimed loudly. “I’m never touching that little so and so again.” Diane held her tongue.

A couple of days later, Diane had to leave the country on a family emergency. Cecilia and I became Frijolito’s reluctant keepers. By now he was known as “el asesino,” the killer squirrel. The first couple of days Cecilia managed to lure him into the cage with food and close the door so he could sleep inside. The third night he didn’t come in, nor the next, nor the next. The following morning, I found him sitting on top of his cage. He looked tired, hungry, and somewhat bedraggled from his three-night jaunt in the wild. I felt sorry for him, and when he wiggled his nose, I held out my hand. “He needs a little affection for reassurance,” I thought. Frijolito grabbed with his claws and sunk his incisors into the vein on top of my hand. When I jerked my hand away the squirrel came with it, his claws penetrating my flesh. I shook my hand, his claws tore loose, and he fell to the ground. Blood poured from my hand. “Never again,” I thought. But then I had said that before.

Diane consulted with a wild animal veterinarian, while I observed the behaviour of wild squirrels. Together we figured out what went wrong. When a young animal imprints on a substitute mother of a different species, it apparently comes to believe that it is a member of that species. In other words, Frijolito thought he was people. If you observe squirrels in the wild, you will notice that they aren’t very social. The only times you see two or more together are: a.) young with their mother, b.) immature litter mates, c.) males and females during mating season. At any other time, squirrels stake out their territories and attack any other of their own species that comes near. Frijolito’s territory included our house, and all humans that came near were invading his territory. All except Diane; she was his mama. This scenario was further complicated by raging levels of testosterone in his adolescent blood stream.

A few days after Diane’s return, I walked into the kitchen, passing about a meter from Frijolito, who was on the counter. He leapt into the air, landed on my right arm, and dug in his claws. I batted him with my left hand, but he bit my finger and ran up my shoulder to the top of my head where he scratched and bit my bald spot, drawing more blood. Again, I batted him and received a bite on my right hand. He landed on my back in a flurry of biting and scratching. Finally, I shook him loose and onto the floor. Diane grabbed him up, protecting him from my fury. “Diane, that squirrel has to go” I shouted, and stomped out of the kitchen.

With the help of Ronald, a Hacienda Barú guide, Diane took Frijolito to a nice forest about two kilometers from our house and released him, in the hope he would go wild. He was last seen in the treetops romping and playing.

There is, of course, a lesson to be learned here. If a wild baby is separated from its mother and left to die, that is simply nature’s harsh way. By overriding Mother Nature’s wishes and saving the helpless baby we leave ourselves vulnerable to numerous unanticipated problems.

Jack Ewing was born and educated in Colorado. In 1970 he and his wife Diane moved to the jungles of Costa Rica where they raised two children, Natalie and Chris. A newfound fascination with the rainforest was responsible for his transformation from cattle rancher into environmentalist and naturalist. His many years of living in the rainforest have rendered a multitude of personal experiences, many of which are recounted in his published collection of essays, Monkeys are Made of Chocolate. His latest book is, Where Jaguars & Tapirs Once Roamed: Ever-evolving Costa Rica.