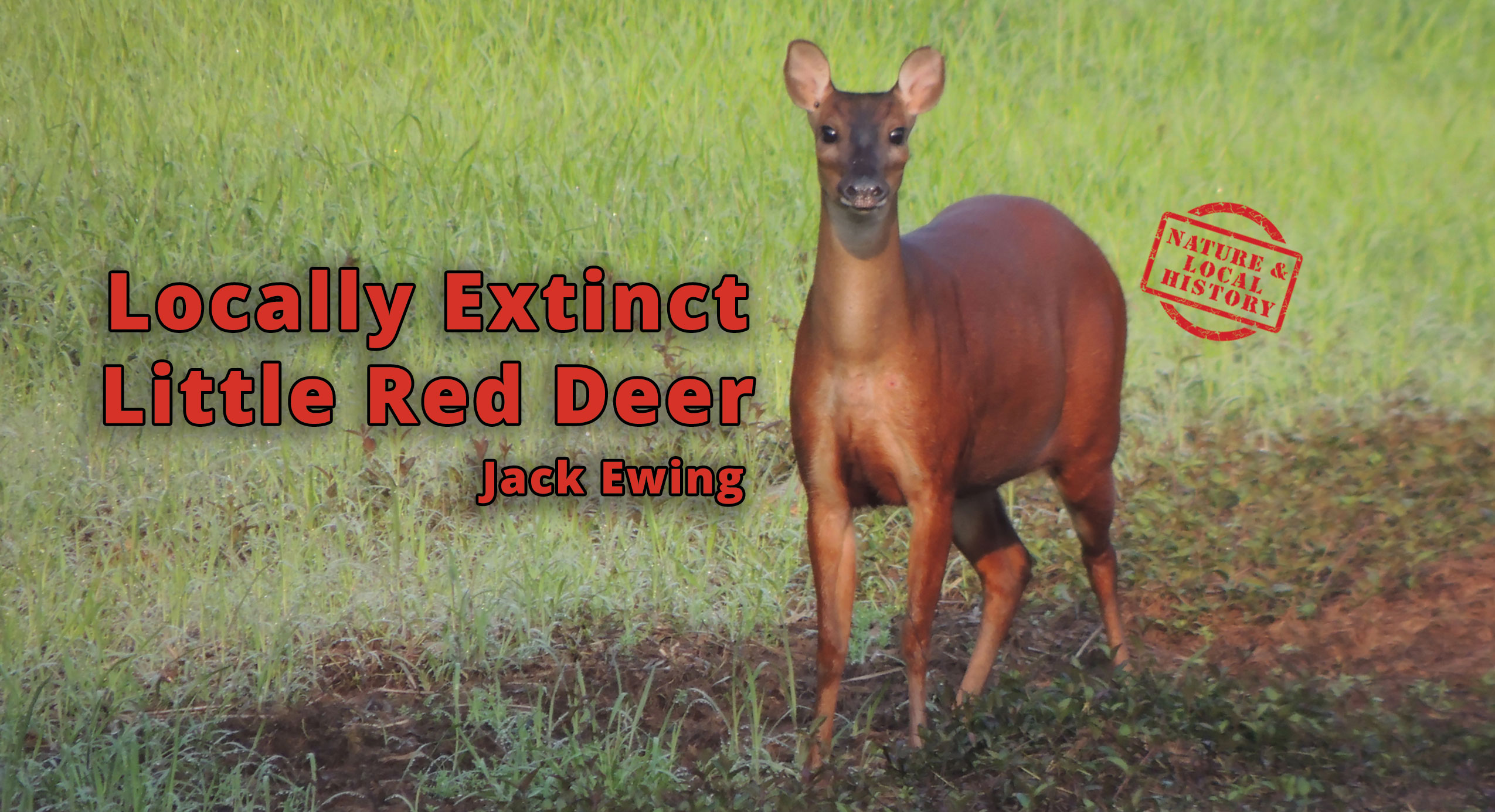

Locally Extinct Little Red Deer

In Spanish they are called Cabros de Monte or simply Cabritos, meaning Jungle Goats or Little Goats respectively. Non forked antlers in the males resemble goat’s horns. Red Brocket Deer (Mazama americana) are locally extinct in much of their former range. During my 52 years of living in the country, I have seen one, and that was in the Corcovado National Park. I believe they are found in Carara National Park as well. The old timers from the south Pacific zone of Costa Rica remember the days when there were many of them.

One story I have heard about hunting brocket deer in the 1950s tells of a hunter who was driving from San Isidro to Dominical and saw a group of the little deer near the village of Barú. Stopping his jeep, the hunter retrieved his rifle from the back seat, leaned it across the hood, and shot every single one of the deer, about 20 as the story goes. Considering that the story is probably an exaggeration, I think there is enough truth in it that we can assume that 60 to 70 years ago there were a lot of brocket deer in the area around Hacienda Barú, and that large numbers of them were killed by hunters until the population dwindled down to nothing. I came to Hacienda Barú 50 years ago and only heard mention of brocket deer from older friends, employees, and neighbors. When they were mentioned, it was always in the past tense.

One story I have heard about hunting brocket deer in the 1950s tells of a hunter who was driving from San Isidro to Dominical and saw a group of the little deer near the village of Barú. Stopping his jeep, the hunter retrieved his rifle from the back seat, leaned it across the hood, and shot every single one of the deer, about 20 as the story goes. Considering that the story is probably an exaggeration, I think there is enough truth in it that we can assume that 60 to 70 years ago there were a lot of brocket deer in the area around Hacienda Barú, and that large numbers of them were killed by hunters until the population dwindled down to nothing. I came to Hacienda Barú 50 years ago and only heard mention of brocket deer from older friends, employees, and neighbors. When they were mentioned, it was always in the past tense.

A visiting biologist saw a buck brocket deer in 1996, and one of the Hacienda Barú guides saw one that same year in the same area. It was possibly the same animal. I saw some scat and footprints about that same time and in the same part of the hacienda. No, brocket deer, scat, or footprints have been seen since.

I started working with trail cameras about 15 years ago and have never captured a photo of one. The environmental organization ASANA monitors wildlife with trail cameras throughout the area within the Path of the Tapir Biological Corridor which comprises a strip of land about 80 km long and 15 km wide along the coastal ridge between the Savegre River and the Térraba river, and during the five years they have been monitoring with cameras, have never captured a photo of a brocket deer. I think it is a pretty good bet that the species is locally extinct.

There is a small but stable population of white-tailed deer in the biological corridor, so why wouldn’t there be any brocket deer? The two species feed on different things, white-tails mostly on leaves, and brockets mostly on fallen fruit and seeds, so there isn’t much competition for food, and both types of sustenance are plentiful. Though there is a slight difference in size 30 kilos for the white-tailed and five kilos less for the brockets that should not necessarily be an advantage. In fact, the smaller, straight antlered brockets have the advantage of being able to lower their heads and barge through thick vines and undergrowth. Brocket deer do have a fatal habit of running a short distance when startled and then freezing, making themselves a perfect target for a hunter with a gun or an easy catch for a pack of hunting dogs.

There is a small but stable population of white-tailed deer in the biological corridor, so why wouldn’t there be any brocket deer? The two species feed on different things, white-tails mostly on leaves, and brockets mostly on fallen fruit and seeds, so there isn’t much competition for food, and both types of sustenance are plentiful. Though there is a slight difference in size 30 kilos for the white-tailed and five kilos less for the brockets that should not necessarily be an advantage. In fact, the smaller, straight antlered brockets have the advantage of being able to lower their heads and barge through thick vines and undergrowth. Brocket deer do have a fatal habit of running a short distance when startled and then freezing, making themselves a perfect target for a hunter with a gun or an easy catch for a pack of hunting dogs.

The two main causes of local extinction of mammals during the last century have been deforestation and hunting, and both seem to have played a role in eliminating the red brocket deer from much of its former range. Who knows why?

The two main causes of local extinction of mammals during the last century have been deforestation and hunting, and both seem to have played a role in eliminating the red brocket deer from much of its former range. Who knows why?

A biologist friend of mine gave me the photos shown here, which were captured by a trail camera in the Amistad International Park. He has about 80 cameras located in southern Costa Rica which support his ongoing, large mammal, research project. “Only the cameras at higher altitudes capture photos of brocket deer”, he told me. All the sources I have checked give the maximum altitude for the species as 2800 meters (9186 feet), yet these photos probably came from over 3000 meters (9842 feet). The executive director of ASANA told me the same thing, “The brocket deer only appear at the upper end of their range and above,” she assured me.

In the last 30 years much of the Path of the Tapir has been rewilded and secondary forest now covers much former pasture and farmland. Populations of some species such as tapirs and jaguars, that a few short years ago seemed to be on the road to extinction, are now markedly increasing. Tapirs have been sighted within the corridor near the northwestern end. Hopefully red brocket deer will join them in their path to recovery.

In the last 30 years much of the Path of the Tapir has been rewilded and secondary forest now covers much former pasture and farmland. Populations of some species such as tapirs and jaguars, that a few short years ago seemed to be on the road to extinction, are now markedly increasing. Tapirs have been sighted within the corridor near the northwestern end. Hopefully red brocket deer will join them in their path to recovery.

Jack Ewing was born and educated in Colorado. In 1970 he and his wife Diane moved to the jungles of Costa Rica where they raised two children, Natalie and Chris. A newfound fascination with the rainforest was responsible for his transformation from cattle rancher into environmentalist and naturalist. His many years of living in the rainforest have rendered a multitude of personal experiences, many of which are recounted in his published collection of essays, Monkeys are Made of Chocolate. His latest book is, Where Jaguars & Tapirs Once Roamed: Ever-evolving Costa Rica.