Sighting Felines in the Wild

Experiencing the sight of a wild feline is about the most exciting thing that can happen to a nature enthusiast in Costa Rica. Most humans share a fascination with cats, whether it be the tiny Oncilla (Leopardus tigrinus) the smallest cat in Costa Rica at 2 kilos, or the enormous Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris), at 240 kg, the largest cat in the world. As they are naturally secretive and wary of humans, seeing a wild feline is not an everyday occurrence. We have five feline species at Hacienda Barú.

I have lived here for 47 years and have only seen one, the Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi), which I have seen on multiple occasions. One of those sightings was particularly memorable. A neighbor who lived close to the lodge bought some young chicks to fatten for meat for the dinner table. They grew quickly and soon the roosters among them began to crow. I know of no sound more irritating than the crowing of an adolescent rooster. It seemed like there was a competition among them, and each day they started a little earlier and crowed a little louder. Soon the racket began shortly after midnight. Of course our guests complained about it, but the neighbor, Ricardo, was uncooperative. One day I saw two jaguarundis cross the driveway heading toward his chicken coop. Word soon got out that they had killed a couple of chickens. Knowing that Ricardo would try to kill the cats, I called the wildlife department and asked if a game warden could come and have a talk with him. One happened to be in the area and stopped by that same afternoon. He told Ricardo that if anything happened to the pair of beautiful black cats they would know it was him, and that the fine would be enormous. Ricardo killed all the young roosters that same day, and put them in the freezer. I don’t think that these beautiful black cats are seen more frequently than other felines because they are more numerous, rather it is because they are diurnal, less wary of humans, and spend most of their time on the ground. At 5 kg the jaguarundi is the third largest of the five Hacienda Barú species.

I have lived here for 47 years and have only seen one, the Jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouaroundi), which I have seen on multiple occasions. One of those sightings was particularly memorable. A neighbor who lived close to the lodge bought some young chicks to fatten for meat for the dinner table. They grew quickly and soon the roosters among them began to crow. I know of no sound more irritating than the crowing of an adolescent rooster. It seemed like there was a competition among them, and each day they started a little earlier and crowed a little louder. Soon the racket began shortly after midnight. Of course our guests complained about it, but the neighbor, Ricardo, was uncooperative. One day I saw two jaguarundis cross the driveway heading toward his chicken coop. Word soon got out that they had killed a couple of chickens. Knowing that Ricardo would try to kill the cats, I called the wildlife department and asked if a game warden could come and have a talk with him. One happened to be in the area and stopped by that same afternoon. He told Ricardo that if anything happened to the pair of beautiful black cats they would know it was him, and that the fine would be enormous. Ricardo killed all the young roosters that same day, and put them in the freezer. I don’t think that these beautiful black cats are seen more frequently than other felines because they are more numerous, rather it is because they are diurnal, less wary of humans, and spend most of their time on the ground. At 5 kg the jaguarundi is the third largest of the five Hacienda Barú species.

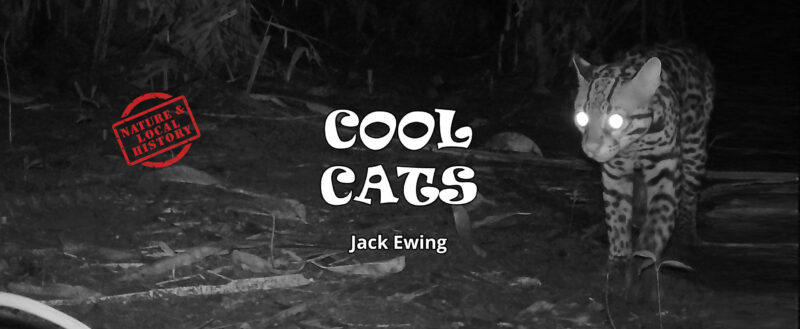

Although I have never seen one, the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) holds a special place in my heart. It is responsible for me becoming an environmentalist. In 1974, when Hacienda Barú was a cattle ranch, the cowboy killed an ocelot. It came around his wife’s chicken coop, his dogs chased it up a tree, and he shot it out of the tree. I had hunted deer and ducks in Colorado, where I grew up, and didn’t have any problem with hunting, but the sight of that beautiful spotted cat’s dead body laid out on the porch of the cowboy’s house affected me deeply, to the point that I gave up hunting and began a long arduous struggle to stop illegal hunting on Hacienda Barú. After many years and many helping hands, the result is the Hacienda Barú National Wildlife Refuge, where all the wildlife now feels much more secure than before. My wife Diane has seen two ocelots, all of our guides and park rangers have seen at least one, and our guests sight them a couple of times each month on the average. Both adults and kittens appear on our trail cameras at multiple locations. I feel that the population is healthy and stable. At 12 kg the ocelot is the second largest feline on the hacienda.

According to The Mammals of Costa Rica by Mark Wainwright, the Puma (Puma concolor) weighs around 50 kg, making it by far the largest feline at Hacienda Barú. Though the Costa Rican puma is slightly smaller than the north American cougar or mountain lion, they are all the same species. The two populations are pretty much isolated from one another and the northern variety feeds mostly on large game like deer and elk, while our pumas never kill anything larger than a deer, and most of their diet consists of peccary, opossums, raccoons, coatis, and even smaller. For that reason natural selection has favored larger cats in the north. Pumas were abundant for the first part of the last century. They were all killed off in the 1940s and 50s by farmers and ranchers and have only recently returned. The first sighting on Hacienda Barú was in 2009 by a couple who was walking on one of our trails and came face to face with a pair of young pumas. Park rangers sometimes see them near the beach during turtle season. They don’t bother the turtles, but hunt the raccoons, coatis, and dogs that dig up the turtle eggs. The population has grown to the point that we capture two or three photos of pumas on the trail cameras each month.

According to The Mammals of Costa Rica by Mark Wainwright, the Puma (Puma concolor) weighs around 50 kg, making it by far the largest feline at Hacienda Barú. Though the Costa Rican puma is slightly smaller than the north American cougar or mountain lion, they are all the same species. The two populations are pretty much isolated from one another and the northern variety feeds mostly on large game like deer and elk, while our pumas never kill anything larger than a deer, and most of their diet consists of peccary, opossums, raccoons, coatis, and even smaller. For that reason natural selection has favored larger cats in the north. Pumas were abundant for the first part of the last century. They were all killed off in the 1940s and 50s by farmers and ranchers and have only recently returned. The first sighting on Hacienda Barú was in 2009 by a couple who was walking on one of our trails and came face to face with a pair of young pumas. Park rangers sometimes see them near the beach during turtle season. They don’t bother the turtles, but hunt the raccoons, coatis, and dogs that dig up the turtle eggs. The population has grown to the point that we capture two or three photos of pumas on the trail cameras each month.

A Margay (Leopardus wiedii) has never appeared on one of our trail cameras, and there have only been two sightings on Hacienda Barú, both by our guides and the guests they were guiding. Most of the margay’s time is spent in the tree tops where they lead a solitary nocturnal life. One source says that they only come to the ground to defecate and move across a gap to another tree. At 3.5 kilos, this species is the second smallest on Hacienda Barú.

A Margay (Leopardus wiedii) has never appeared on one of our trail cameras, and there have only been two sightings on Hacienda Barú, both by our guides and the guests they were guiding. Most of the margay’s time is spent in the tree tops where they lead a solitary nocturnal life. One source says that they only come to the ground to defecate and move across a gap to another tree. At 3.5 kilos, this species is the second smallest on Hacienda Barú.

The Oncilla (Leopardus tigrinus), sometimes called the “littler tiger cat”, is even smaller than the Margay, weighing a meager 2 kilos. None of our staff has ever seen one, and The Mammals of Costa Rica says that they aren’t found in this part of the country. Two sightings, both by biologists, at different locations, and about a year apart give us confidence that they do exist on the refuge. Along with the rest of the spotted, wild felines, they were hunted heavily in the 1960s for the fur trade. It takes 24 oncilla pelts to make a fur coat. Fortunately there is no longer a market for fur coats, and hunting pressure has diminished to almost zero.

Prior to 1940, Jaguars (Panthera onca) were often seen at Hacienda Barú and throughout the area that is now known as the Path of the Tapir Biological Corridor. As their territory was invaded by humans and their habitat destroyed for farming and ranching, they turned to domestic animals for food. Pigs seemed to be their favorite, but calves, chickens and dogs were also on their menu. The last jaguar in this area was killed in the mid-1950s. Hopefully they will return across the biological corridor one day as more habitat is restored and people learn to appreciate our wild heritage. I have never seen a jaguar in Costa Rica, but I was fortunate enough to visit the Pantanal National Park in Brazil with the express purpose of seeing one in the wild. My daughter Natalie sighted the first one a second or two before me. “Oh daddy it’s huge!” she exclaimed. And they really are huge. At around 80 kg they are considerably bigger than a puma and are undisputedly the largest feline in Costa Rica. The photo shown here is from Brazil.